Hi, my name is Max, and I’m the founder and CEO of the corporate startup studio ADP (Admitad Projects). It so happened that I traveled a rather rare path: creating a “startup factory” on a large scale — up to 350 people in the team, around $30 million in total investments, four countries where we launched businesses, more than 20 ventures older than the seed round (most started from scratch), and hundreds of ideas tested at even earlier stages.

I’m writing this article for two reasons:

- To document this life stage while my memories are still fresh, “close the gestalt,” and turn the page.

- To share the data and advice I wish I’d had at the beginning of my journey. If it makes life easier for the next travelers, I’ll be happy.

I’ve already written in detail elsewhere about the philosophy and mechanics of running a startup studio (I’ll leave links), so here I’ll focus on the main milestones, outcomes, and reflections on what we did right and what we should have done differently. In hindsight—we all get smarter afterward :).

Intro: Background and Context Behind Creating the Startup Studio (in two words)

In 2010, we launched admitad.com, a business in internet marketing, specifically partner networks. Essentially, we connected companies that have an audience with publishers (companies) that need that audience. We structured their interactions using performance-marketing models: Cost Per Action, Revenue Share, Cost Per Sale, etc.

Our main clients were — and still are — large companies in eCommerce, travel, fintech, gaming, online services, and so on. We put our biggest bet on cross-border operations, i.e., international partnerships. For example, we’d help a German company expanding into India find an audience in that new market, or a Polish company get more clients in neighboring countries or further east.

I was a co-founder in that company and the first CPO, CMO—meaning I was responsible for both the product and its promotion.

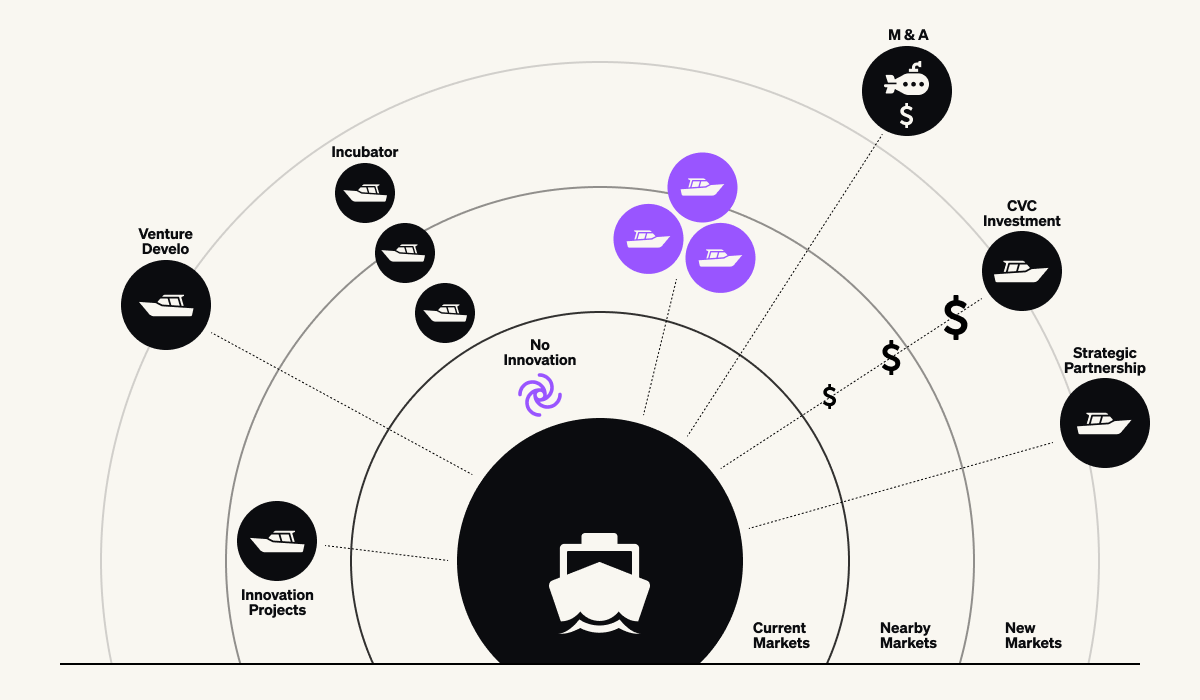

As the company grew and wanted to develop further, we tested different ways to do so:

- Creating new products in-house from scratch.

- Expanding into new geographies.

- Investing via a corporate venture fund.

- M&A (acquiring other companies).

I had a hand in items 1, 3, and some of 4. The venture fund did rather well, yielding a couple of very successful projects.

In 2018, we decided we wanted to test and launch even more new products — but doing this inside the main company was slow and expensive. We needed a more independent format, so we began building one from scratch, using the product and business competencies we had at the time.

Only a year or year and a half later did we learn about the existence of terms like “Startup Studio,” “Venture Builder,” “Company Builder,” etc. It’s hard to search for what you don’t know exists or what it’s called :).

Startup studios are a type of business that produces/creates other businesses. Variations are plentiful, depending on whether the goal is to develop ventures for the fundraising/VC market or for other purposes. The tool itself is quite flexible; there are hundreds of startup studios worldwide, almost all different, so there’s no single standard.

In our case, it went pretty well. In 2019, we kicked off the startup studio project known as Admitad Projects (ADP).

The First Year: Launch

Our initial investment thesis and constraints were as follows:

- We build businesses with a potential annual revenue of at least $10 million (the parent company was already sizable, so we wanted to launch things that would be noticeable in the overall P&L).

- We start only in the Russian market. At that time, our core team was in Moscow, so it was easier to bring people together, and our business network in the country was strong, meaning we could help projects more effectively.

- We don’t bring in external investors: we use our own (corporate) investments to move faster and avoid conflicts of interest.

These three key decisions later came back to bite us. As the saying goes, it’s tough to compensate for strategic miscalculations with tactical successes. But at that point, we just didn’t know better.

Another important constraint was to create “cash cows,” not projects for exit. In Eastern Europe, the culture of major M&A or IPOs is basically nonexistent, so it made no sense to aim for a classic venture-style product. Whether that is good or bad depends on what you want and your exit-game strategy. I strongly advise you to think everything through a thousand times and calculate thoroughly because this choice will define almost everything else: which projects you accept, which people you hire, which services you need, the project cycles, etc. Changing it later gets complicated.

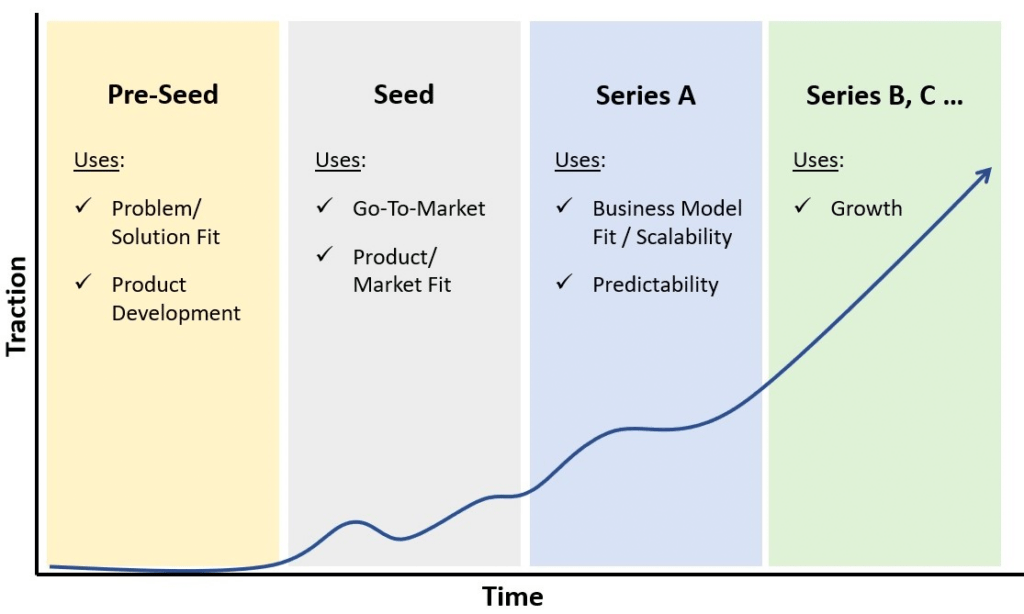

We also made one more decision at the time — to model internally the venture capital market. That turned out to be excellent and worked well throughout the studio’s lifecycle.

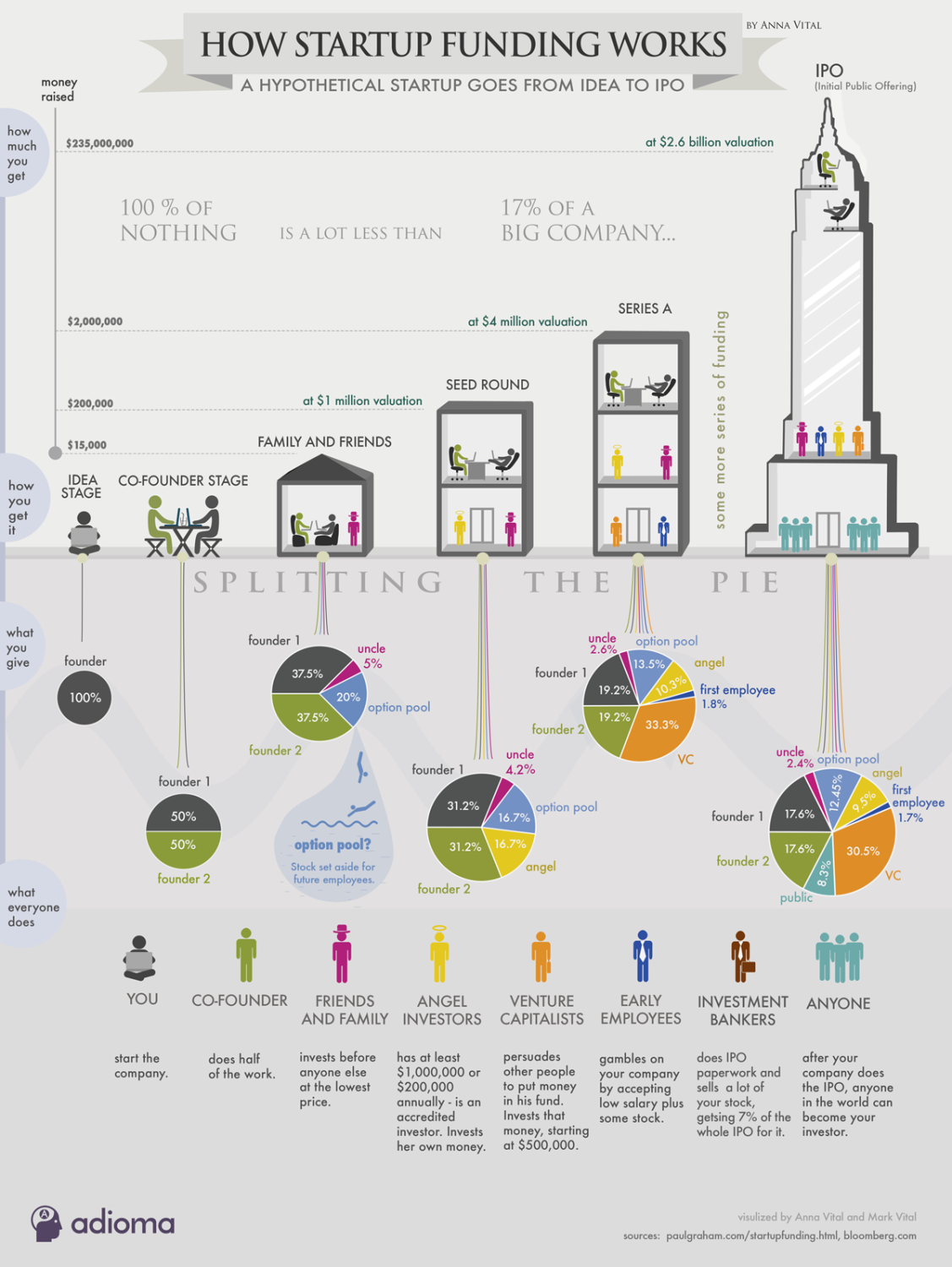

What does it mean? In the “wild” world, any startup goes through maturity stages: idea, pre-seed, seed, Series A, B, etc. We set up the same logic internally: the younger the project, the leaner and more frugal it is, with the smallest team possible. As it matures and (if) succeeds, it raises money from the corporation’s investment committee and scales up.

Crucially, the studio team provided pre-seed rounds themselves, while bigger rounds (seed+) came from the corporation’s investment committee.

What we should have done: Actually, the decision worked fine. If you’re creating a startup studio without a corporate backer, it would be ideal for the studio itself to provide the seed round, so it can maintain full control and responsibility from zero to product-market fit.

Starting in summer 2018, we gradually built a team and tried our first approaches for testing lots of ideas so we could pick out the best for building and scaling businesses. At the beginning of 2019, we celebrated the official opening of the studio and agreed internally that we’d consider it a success if five new projects secured seed investment from the corporation that year (the decision to invest was made by different people outside the studio, so it felt like a relatively unbiased metric).

By the end of 2019, a whopping eight of our newly created projects received seed-level funding to continue development — an excellent outcome.

And how else could we have done it? For the first year, the metric of “successfully passing investment committees” is indeed good. I’d do it that way again. Demanding profits in the first few months is harmful because you’ll just end up with very small “agency-type” businesses, not big, scalable product-type ones, which we actually wanted. Plus, going through investment committees is a good way to align the investor and the studio.

Our total spend in that first year was about $6 million (including the studio team and the investment rounds we gave to projects).

The Second Year

Then came 2020. Internally, we split into three large blocks: Incubator (creating new projects from scratch), Accelerator (working with seed+ stage projects), and Services (general support for every project—from design and development to marketing, recruitment, and user research).

By the way, we split the Services into Soft Office and Hard Office, which turned out to be a brilliant idea. Soft Office was the creative side, where mistakes are encouraged and strict control isn’t necessary. Hard Office covered accounting, finance, and legal matters—areas where mistakes can be costly, requiring more rigorous management.

I described this in more detail in a separate article.

While we were producing and testing new ideas, some older projects had already received large investments. So for the Incubator, we kept the same metric: how many new projects pass the investment committee? Meanwhile, the Accelerator was all about revenue growth. We wanted to triple revenue year over year. We hit that target: by the end of 2019, our portfolio’s Q4 revenue was $200k, and by Q4 of 2020, it was $800k. In total, we earned $2.5 million in 2020.

Spending in the second year remained about $6 million (studio team plus investment rounds). We were growing beautifully, and both we and our investor were more than satisfied.

But that same year, our first trouble arrived: COVID and lockdown forced everyone to go remote.

By the end of the year, the corporate investor decided it was time to change one of the original constraints: rather than launching projects in Eastern Europe, we’d focus on international markets to earn revenue in foreign currencies.

How it should have been: If there are compelling reasons, then you do what you must. But pivoting geographies is extremely tough. We had to kill a bunch of early-stage projects that were focused on the “wrong” geos and restructure about half of our services to fit the new markets.

How Much Does It Cost to Build Startups via a Startup Studio?

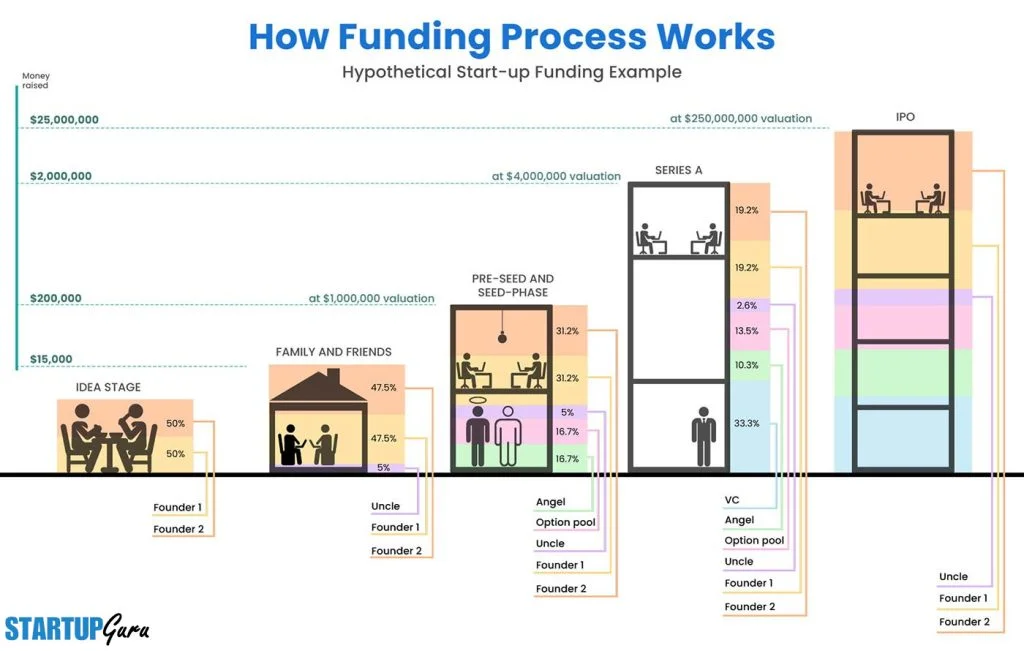

One interesting question that kept coming up was how to measure success before we’d had any exits.

The best metric we found to compare apples to apples was the cost of acquiring 1% ownership in a seed-stage startup for the investor.

Two main options exist:

- You invest as an angel or venture fund, paying $15k–$35k per 1% of a startup at seed (depending on the valuation).

- Through the startup studio instrument, the investor could essentially buy 1% of a similarly mature project for $10k–$12k.

Among comparable companies in our region, we were considered one of the best. If you plan to replicate what we did, discount our numbers a bit. In any case, it’s at least not more expensive than the market would charge, and often cheaper. But you need the right team and a clear understanding of the tool itself — being an angel investor is definitely simpler.

The Third Year: Integration

Welcome to 2021. Our core team moved to Germany, to the corporation’s headquarters.

The number of projects kept increasing, revenue was up, and the demand for further funding also rose. We then faced the question of how to ensure continued financing. We could go to the external market to raise capital, or have the corporation invest in a separate legal entity. But that latter route was costly: you first have to pay corporate profit taxes, then invest what’s left.

During COVID, going out to fundraise with Eastern European assets didn’t sound great. We wanted as much money as possible to go straight into growing projects, so we decided the most efficient plan was to merge the studio with the corporation (in other words, the corporation effectively did an M&A deal with the previously autonomous startup studio).

For the corporation, it was a good deal: it acquired six seed+ projects using a minimum revenue-multiple valuation from last year. That approach is more advantageous to the buyer than the seller at such an early stage.

Those six projects became business units within the corporation and went under new management. We can consider that the end of the original startup studio era because a different team took over further development.

How it should have been: M&A is always complicated: different cultures, processes designed for different tasks and risk levels, managers used to a certain project type who often lack deep knowledge of the new ventures’ business models. Therefore, whenever possible, keep the founding team in charge to maintain continuity of responsibility and preserve essential context.

All of 2021 was spent on integration, plus restructuring services for new geographies, reformatting ownership shares, buying out shares from the studio team and founders to avoid conflicts of interest, and so on. We also had our first wave of layoffs, based on the assumption that many services were duplicated in the corporation and thus unnecessary.

That, too, turned out to be a mistake. A lawyer who’s used to working in a startup studio is a different animal from a lawyer in a large company. It’s not about better or worse—just different. And what works well in a big company might not suit a small startup, and vice versa.

How it should have been: If you’re doing a startup studio, make sure all the services truly belong to you and are tailored to your niche. It’s tough for a startup studio to survive inside another large organization without autonomy. Folks from the big company may be shocked by the high risks startup teams are willing to take; while the startup teams, in turn, can’t understand why something that used to take one hour now takes five days.

Are “Ordinary” and “Corporate” Startup Studios the Same Thing?

No, they have different goals, different ways of evaluating projects, and different decision-making principles. Once again, let me suggest you speak with a large number of people who’ve taken a similar path. There are plenty of them nowadays, and you don’t need to reinvent the wheel.

For illustration, here’s one lesson we learned (which wasn’t obvious at the outset):

What counts as a “good project”? If you’re an independent startup studio, it’s clear enough: the project must generate revenue, show growth potential, and have a solid chance of a profitable exit. But if you have only one investor — a corporation — it might add extra constraints: the corporation’s preferences, habits, and strategy. For instance, maybe your project is scaling fast, hits a ceiling, then needs to tweak its business model and pivot to a different niche. As an independent studio, you’d say: “Great, let’s do it.” But in the corporate scenario, that pivot might be uninteresting or unfamiliar to them, and they might say, “Why invest in something so far from our core business?” — and shut it down.

Is that right or wrong? I won’t judge. It’s simply a factor you must recognize from the start.

Fourth and Fifth Years: Optimization

Early 2022 saw the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. Our corporation had always been about cross-border, internationalism, and “building bridges” between countries. Now, we had to tear that down and localize things. And this is aside from the urgent matter of ensuring employee safety (many were directly affected). Meanwhile, our team was highly distributed across different countries since the COVID era.

The corporation’s revenue took a major hit, so we had to optimize everything, including business units that wouldn’t break even in less than a year. Yet we adapted and continued launching new business units in various places—from India and the UAE to the U.S.

In 2023, the startup studio’s expenses were also cut significantly, especially for new business creation, as that’s the most expensive and risky segment (it can take 2–4 years from idea to visible revenue at the corporate level). We stuck to developing only the existing portfolio.

During this time, one of our first-batch projects grew its net revenue to $400k a month. A few others that were born in the studio raised new Series A+ internal investment rounds.

What Happened Next?

By early 2025, of all the projects built in the startup studio, three remain in the company and continue developing at mature stages scaled to a few geo's, while two spin-offs and now operate independently outside the corporation.

Did the whole thing pay off? Altogether, including follow-up rounds, we invested around $25–$30 million. Some money was recovered via “double economics” (more about this approach here and here), and the surviving projects on paper are now valued higher than the total investments. But there’ve been no real exits/dividends yet, so it’s too soon to say. The result isn’t what we originally expected — that’s on me, and I’m ready to accept the tomatoes you throw.

In 2024, the company chose to restart its corporate venture fund based on the lessons learned and launched an internal Venture Client model. We returned to it as a simpler format requiring less working capital and a smaller team while still recovering from the war’s impact.

What Am I Doing Now?

I’m still at Mitgo (the group that includes Admitad), working on this venture fund and “reinventing investments” as a product, adapting the lessons learned to our current needs, and pushing the idea of “double economics” in investments (I wrote more about it in a separate article and here).

I’m also in charge of innovations for our core audience — publishers, online entrepreneurs, and influencers. If you have products that could make their lives better, drop me a line.

What Would I Do Differently?

I wrote a separate pieces on this a couple of years ago(first and second articles), but let me reflect again:

- Spend more time on planning, choosing the market, niche, and constraints. And make sure I have a long-term commitment that no one changes that plan for at least three years.

- Go super narrow with the startup studio. Pick one niche where you can offer something besides money, and never step outside it. Then you get that compounding effect of data, tech, team, and expertise, and the studio’s “muscle” really shows. And I'll exploit "the double economy idea" as much as I can from the start.

- Clearly define your entry and exit points: Where does the studio’s job start and end? I see two workable approaches: Maximal. The studio holds a large stake (up to 80%), so it’s effectively your business, you’re responsible for the outcome, and you just have additional services/partners to help. It’s a semi-founder mode for the entire project lifetime. Minimal. You provide certain services for a fixed period (like nine months), get a small equity stake (up to 10%), and that’s it—the project is then on its own.

- Fix who makes the key decisions — whether to give a new investment round, whom to hire as CEO, whether to close the project. And like in any venture fund, plan to reserve half of your capital for follow-up rounds in the projects you initially back. If you have $10 million, don’t split it into ten $1 million chunks for ten companies. Instead, start with five companies for $5 million total and keep $5 million in reserve for the most promising ones — even if your sponsor’s strategy changes halfway through.

- Agree in advance on the main end-game scenario. How do you exit a project if it’s corporate? When does it buy you out, and at what valuation model? If you plan to go external, what is your fundraising policy, and start it as early as possible.

Valuable Lessons We Learned

- Equity percentage directly correlates with your responsibility for a project’s success. It’s bad when you have a small stake but do all the founder’s work. Or the opposite: the founder has 5%, but you’re expecting them to handle everything themselves.

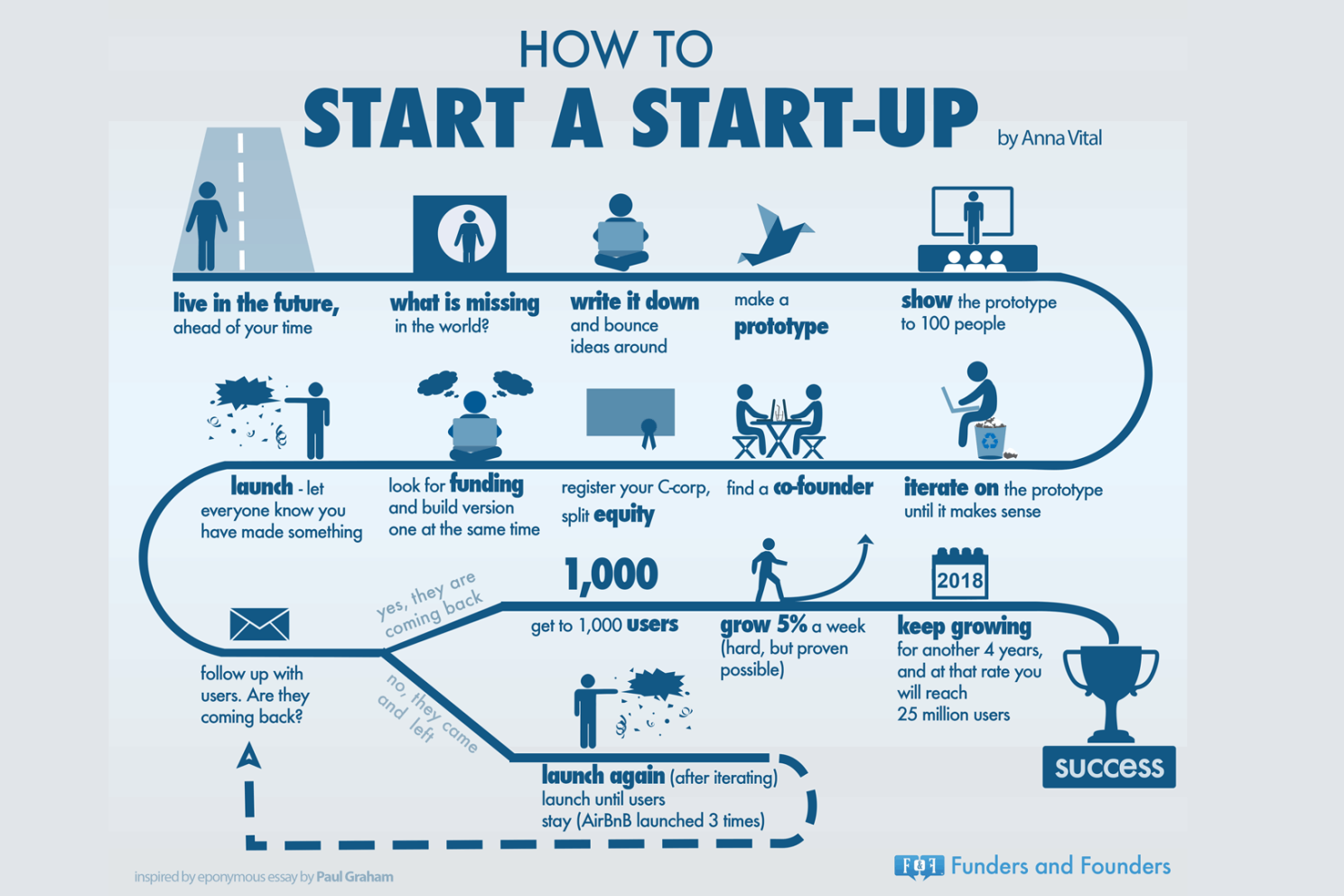

- Development is evil, inevitable evil. The later you start coding, the better. It’s cheaper and faster to move forward. Almost all business ideas can be tested partially without writing a single line of code. The more data you collect before coding, the better the final product will be.

- Any business can be successful — it’s a matter of attempts, people, and resources. You can tweak those levers to eventually find a winning formula in almost any niche. The question is whether you have the patience. Often the founder loses faith first, even if the idea is still promising. And sometimes it’s better to keep exploiting the experience you’ve gained rather than start from scratch.

- Often, the “idea” doesn’t matter that much. Out of the 100+ companies we started, the most successful survivors rarely stuck to their original concept. Over 2–3 years, the starting idea inevitably changes, so there’s no need to obsess over it. Market changes are a much bigger deal than idea changes.

If I missed anything about running a startup studio, feel free to ask in the comments.

Other my articles I may recommend if you're interested in corporate innovation and startup themes: